Ukraine: Searching for the Dead

Mobile war crimes investigation teams are collecting evidence across the country to bring perpetrators to justice.

Ukraine: Searching for the Dead

Mobile war crimes investigation teams are collecting evidence across the country to bring perpetrators to justice.

The air is chilly. Viktor Sytnyk smokes and feeds a stray cat as he waits his turn outside a hardware shop-turned-police station. After an hour, he walks into the building to report how his 90-year-old mother died during the Russian occupation of Izyum.

"I don't believe [the Russians] will be punished, but I want my mother to have at least a grave," the 64-year-old former forest ranger said.

To retrieve her body from the mortuary in Kharkiv, 130 kilometres north of Izyum, he needs to go through a number of formalities.

The police station burned down during the occupation, so investigators are gathering evidence of crimes in an empty shopping centre. The town is a shadow of its former self: most buildings are damaged with gaping holes and the main administration office is charred.

Izyum had no internet, gas, or electricity for most of the six months of the occupation. Even now, Viktor barely gets news. A neighbour informed him that a team was taking DNA samples.

Viktor climbs the metal ladder to the second floor. The walls are plastered with photos of store employees — smiling people in party hats celebrating birthdays. The “before” times, another life.

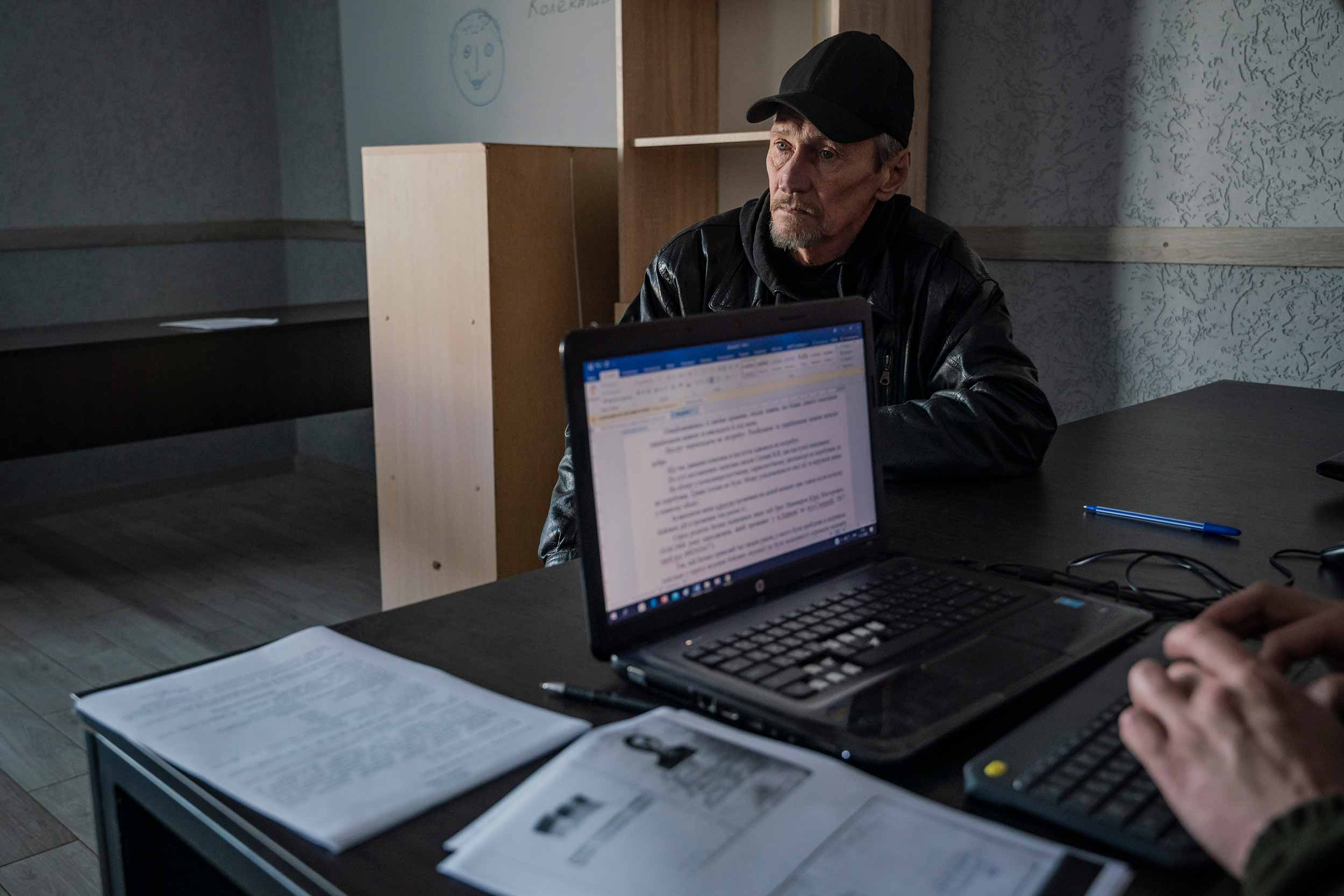

Three prosecutors talk to Viktor, following a standard legal procedure. The testimony needs two witnesses; these are taken from the silent queue of about ten people waiting to report the death or disappearance of their loved ones.

First, Viktor must provide photocopies of his and his mother’s passports, then a DNA sample is taken: cotton swabs are rubbed inside his cheek several times, packed in an envelope and sent for forensic analysis.

Then, as the prosecutor types, Viktor starts relating what happened on May 21.

It was Saturday morning. At about 7am an explosion woke the Sytnyk family. A shell had fallen near their yard, shattering the window in his mother Natalia’s room. Her knee was bleeding, cut by shrapnel.

Viktor rushed to his mother and a neighbour drove them to the hospital where only a single doctor remained to care for patients. Natalia underwent surgery, but when Viktor returned to visit the next day he was told that she had died following a traumatic shock. Her body was lying in the mortuary.

Only one burial service was functioning. By the time Viktor arranged the funeral and returned to the morgue, his mother’s body was gone. He was told that a team organised by the occupation authorities had already taken it to the cemetery.

Such haste was not unusual. Locals report that the installed Russian authorities would receive a budget per each burial, forcing the local service to supply crosses and pit diggers for free. They would then keep the money saved.

The occupation authorities designated a pine forest on the outskirts of the city for the burials. Viktor twice tried to reach the area, but Russians guarding the perimeter prevented anyone from walking in.

After the Russians retreated from the city on September 10, locals could finally access the burial site.

A total of 447 graves were discovered – some with names, others unmarked - revealing the bodies of military and civilian personnel, some with signs of violent death.

Viktor, still stuck in an information vacuum, did not know about the excavations. The investigative team recorded in the report all possible details of his mother's death: her body was buried under cross 353.

As soon as his DNA matches the samples on the database, he will finally be able to care for his mother's grave.

COLLECTING EVIDENCE

To meet the enormous task ahead, mobile war crime investigation teams have been set up and deployed by the prosecutor general’s office.

Investigators have come a long way since the first towns were de-occupied in the Kyiv and Chernihiv region in spring. Now, in the Kharkiv region, various specialists are coordinated into one group and the locations of the region have been divided between them.

Each team comprises three or four experts who inspect the crime scene, record the exhumation process, interrogate witnesses, gather evidence, collect and send DNA samples to laboratories, and fill out all necessary documents.

The teams travel across the de-occupied areas to collect evidence; there are about 28 teams operating in the Kharkiv region alone.

Each story is a separate criminal proceeding and entered into a unified register for investigation. The scale is enormous, with about 46,000 open criminal proceedings for Russian war crimes: as of November 2022, the police had identified 6,600 cases of people shot and tortured by the Russians.

Crimes are filed in three sections: committed on the territory temporarily not controlled by Ukraine, shelling of the civilian population and infrastructure and crimes in the de-occupied territories.

All documented evidence is then sent to the security service to conduct the investigation. Evidence can also be sent to international courts.

In addition to prosecutors and investigators, additional specialists such as forensic experts, photographers and criminologists are called on in case of need.

When mass graves are discovered, mobile teams access the site after sappers have inspected and made it safe. Law enforcement officers then fill in protocols describing the corpses. Any detail is precious: tattoos, clothes, shoes, physical features. The whole process is filmed, including the questioning of the local men forced to work as grave diggers during the occupation.

During the exhumations, a mobile DNA laboratory takes tissues from the bodies.

Investigators come from all over Ukraine and are regularly rotated. Ivan Likhovyn, a Lviv prosecutor, recalls a visit to Izyum in early October to join a team for an assignment.

The exhumation in a village near Izyum found the bodies of two Ukrainian soldiers of 50 and 21 years: their hands tied behind their backs, their eyes covered with an embroidered towel.

“It wasn’t the first time I have seen dead bodies, but here I work not only with murder, this is genocide, deliberate destruction, and torture,” he said. “The sooner we gather evidence, the sooner we can show it in international criminal courts and bring Russia to justice. I have no more emotions — only the desire to work as fast as possible.”

THE MISSING

Many in Izyum had loved ones who simply vanished. Forensic evidence is key to finding them.

For instance, DNA analysis led to the identification of Volodymyr Vakulenko, a young poet and writer in Izyum, who kept a diary about Russian occupation and hid it under a cherry tree in his garden, before he disappeared.

But it is a monumental task. Some 46,000 people lived in Izyum before the war. When Russia took control of the town on April 1, around 17,000 residents remained. Many have not returned, which complicates DNA collection. Investigators have developed an ad-hoc system to allow people to take samples themselves. People have to record the procedure on video, in the presence of two witnesses, and send the materials and written consent to the prosecutor general’s office.

Those still in Izyum can queue at the makeshift police station bringing anything with traces of DNA that could help identify the exhumed: combs, toothbrushes, razors. All possible details are entered into the database and matched with the profiles of unidentified corpses. The procedure is carried out in specialised forensic centres operated by the ministry of internal affairs of Ukraine.

Hanna Vorotna, 65, waits for her turn in silence. Once in, she moves slowly, filling in papers with detailed descriptions of her youngest son Serhii, in his 30s, who she has not heard from for months.

In 2015-16, Serhii fought with ATO, the anti-terrorist operation run by Ukraine’s security forces for four years in Donbas in the wake of the 2014 fighting. As Russia invaded, he joined the self-defence units in Izyum.

“March 27, the wife of another defender told me that Serhii had been killed,” Vorotna recalled tearfully. “It seems that they were being held captive by the Russians in a basement and one of the men managed to escape by changing into civilian clothes.”

Ukrainian officials reported finding at least ten torture chambers in Izyum alone.

Her eldest son, also in the military, was kept in another basement for eight days: the Russians beat him, broke his ribs and took his money and phone before eventually releasing him.

But despite visiting many former detention sites, Vorotna could find no trace of Serhii.

“If he were alive, would he have given news about himself after so many months? I am looking for a way to rebury him, because I can't even put candles in the church.” She apologies for crying.

Local prosecutor Yuliia Chumachenko tries to remain detached as she interviews Vorotna.

She needs to contain her emotions, she said, “Otherwise, it is impossible to work.”