Borodyanka: Still Crying

Residents believe the Russians attacked so viciously because of spirited resistance by the local territorial defence.

Borodyanka: Still Crying

Residents believe the Russians attacked so viciously because of spirited resistance by the local territorial defence.

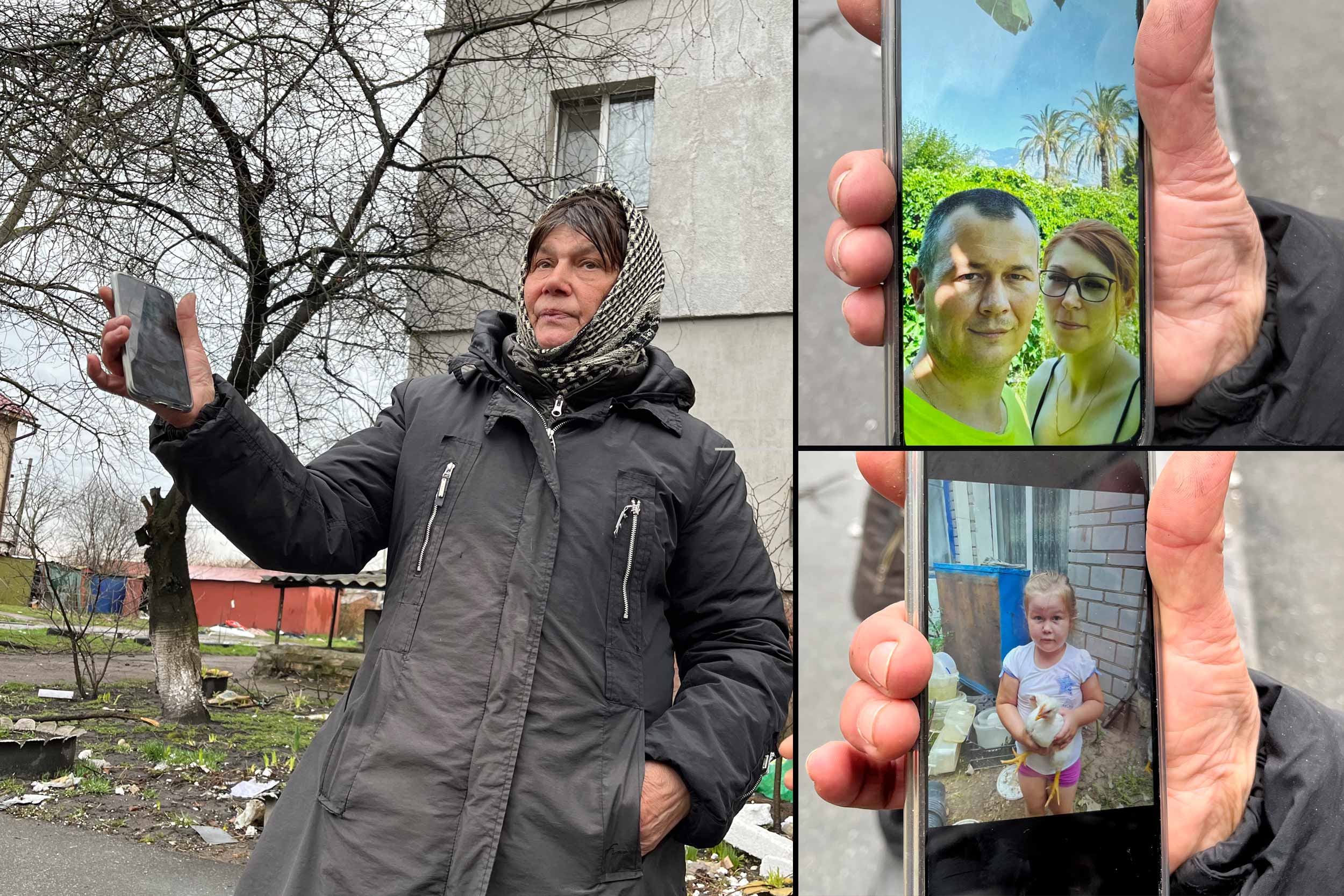

“Goodbye, my beauty, I will cry until I see you again,” Luidmila Smishchuk said to her four-year-old granddaughter Eva as the family left to spend the night at their nearby apartment.

The family were only in town because a bridge to Kyiv, where the parents worked, was out, so they had returned for the night to their home settlement of Borodyanka.

Six weeks after that parting, Luidmila is still crying.

On an overcast Saturday, she waits by the excavation site of the shattered building where her son Vitaliy, his wife Tetiana and their “golden girl” Eva perished when the building was bombed just a few hours after they left her.

That evening, March 1, was to be Borodyanka’s day of horror.

The family had been sheltering in the basement and were buried when the centre of the building collapsed. After the first shell hit, they had spoken by phone, and Luidmila had warned them that the building could fall.

It was their last call. The next shell obliterated the building.

Most of the other residents were sheltering elsewhere. Their own apartment, on the fourth floor but in a different section of the structure, remained intact.

Up and down the street, Russian jets targeted residential buildings, including a major structure opposite the town square, that must now serve as one of the icons of war damage from the Russians’ pointless and vindictive siege of the capital.

Locals estimate 25 or more people may be buried there, and put fatalities across the town at around 200, although it could be much higher. In total, more than 60 buildings were hit, with half of them being fully destroyed.

Ludmila had to endure a month of occupation, until the Russians departed, for any kind of closure. Now she waits while the recovery team use shovels and a backhoe to find Eva and Tatiana’s remains, shifting through the rubble bucket by bucket.

Vitaliy was a surgeon at a specialist clinic in Kyiv; Tetiana, a nurse. His incinerated remains were found this morning.

“You couldn’t recognize anything,” Ludmila said. A photo of the scene shows his body looking like one of the frozen grey figures from Pompeii. Vitaliy was identified by the house keys in his pocket.

Several neighbours and friends wait out in front of the half-destroyed building, while from time to time a resident emerges from the stairway with a large plastic bag or a wrapped blanket full of clothing and other goods, as they move to stay with family or friends elsewhere.

One resident confronted the Russians with a shotgun, shouting, “Slava Ukraini (Victory to Ukraine),” before being shot.

And yet, the town is re-emerging. Only a couple of days earlier, it was an empty moonscape. Now an army of humanitarian aid helpers populate the town square, and a de-mining team goes door-to-door, painting large yellow dots on houses that have been cleared. Excavation workers swarm in their yellow vests and helmets over at least three major destroyed structures, with a large crane working the main wrecked building in the centre.

Borodyanka is at a crossroads, and Oksana Soshko, 50, a member of Luidmila’s extended family, explained that a huge column of 200 Russian tanks had entered the town at the start of the war, travelling down from Belarus aiming for Kyiv. According to some estimates, the number may have been many, many times that amount.

Oksana said Russians terrorised the population from the start, setting up a checkpoint at the town’s entrance with three tanks plus snipers, preventing people from leaving their houses.

They also set about torching the roofs of private homes, including her parents’ house. Living adjacent to the check point, theirs was the first set on fire.

“My parents were hiding in the basement, and were going to burn alive. Snipers prevented anyone from going to help them. I begged them to escape, but my mother said, “They will shoot us, we are staying inside.’”

To buy time, they covered the basement door with a wet cloth and punched a hole in the wall to be able to breathe. Speaking on mobile phones, the parents said their goodbyes to their daughter.

Finally, when the Russians were distracted, a neighbour crawled over and was able to pull the door open and save the couple.

“It was to intimidate us,” Soshko said. They were lucky, but not Eva and her parents.

Borodyanka enjoys a pleasant position above a woodland, but has little else to distinguish it except as a transit point to Kyiv.

Residents believe the town was attacked so viciously because of the spirited resistance by the local territorial defence. Guns had only been distributed days before the war, but they managed to put up a fight.

Their people’s resistance may have been ultimately inconsequential, and some was reckless. According to Valentin Moyseyenko, 72, of the Ukrainian Academy of Agrarian Sciences, in the first days one resident confronted the Russians with a shotgun, shouting, “Slava Ukraini (Victory to Ukraine),” before being shot.

But locals did destroy several vehicles and kill a number of Russian soldiers. A photograph taken by Moyseyenko shows one Russian flat on the ground, his head shot off.

Moyseyenko, whose apartment overlooks the main square, said he saw a Russian airplane circle, target and directly hit the statue in the square of iconic Ukrainian poet Tara Shevchenko.

Now, a choir sings defiant patriotic songs to serenade the excavation workers and add some cheer to the sad town.

To the loss of a few armed combatants and their vehicles, Russia responded with the brutal murder of hundreds, the devastation of more than 60 residential properties and a town forever stained with sorrow.

Luidmila’s daughter wanted to come back to be with her, but her mother refused and said she should leave Ukraine.

“There is no base or anything here,” Luidmila said, showing a photograph on her phone of her granddaughter, with her dramatic thick pony tail. “No one could ever imagine that such a small settlement would be destroyed like this.”

Translation and additional reporting by Anna Serdyuk.