Why Ukraine’s Fight Must Continue

A premature deal would be wrong, not least because we already tried – and it failed.

Two Russians Sentenced to Life for Murder and Looting

The servicemen killed four civilians and took their mobile phones which helped investigators identify them.

Tuesday, 23 April ‘24

This week’s overview of key events and links to essential reading.

The Legacy of the Muhajirs

Award-winning documentary explores ancient traditions though historical records and personal testimony.

Restoring Justice for Ukraine

"This is a great achievement for the entire international community.”

The Afghan Women Journalists Defying the Taleban

Against all odds and despite constant danger, a brave few continue to report.

Women Support Women

How survivors of sexual violence are working to gather testimony for future justice processes.

Tuesday, 16 April ‘24

This week’s overview of key events and links to essential reading.

Russian POW Sentenced for Murder and Looting

The corporal admitted guilt, declined to appeal and requested he be exchanged.

Tuesday, 9 April ‘24

This week’s overview of key events and links to essential reading.

EU Team Advises Ukraine Over Justice Challenges

“The security situation is fluid, the crimes continue to mount and the world’s eyes move on.”

Russian Soldiers Face Trial For Murder of Farmworker

The pensioner, according to the investigation, had asked his assailants not to scare his livestock.

Tajik Migrants Brace for Moscow’s Ire

Their situation has been deteriorating for the past few years, but the Crocus concert hall atrocity has accelerated events.

Tuesday, 2 April ‘24

This week’s overview of key events and links to essential reading.

Ukraine Pursues Genocide Charges

Although the term is currently often used in international politics, the legal complexities are huge.

Highlights from IWPR’s Consortium to Support Independent Journalism in Latin America (CAPIR).

An investigation by Honduras Verifica, a beneficiary of our counter-disinformation programme, revealed the modus operandi of MiNotaHN.com, a website initially launched as a parody of a reputable Honduran media outlet TuNota.com. Within a few months, the portal began to publish pseudo-news pro-government content. Honduras Verifica found that such stories were promoted online by an army of inauthentic accounts on several social media platforms. Various ministers and state institutions have republished, liked or commented on its content. The investigation was re-published by nine Honduran and Central America outlets and the authors interviewed by local media.

A story by Nómadas, a media outlet beneficiary in our in-depth journalism mini-grants programme, revealed how members of the Eyiyoquibo indigenous community in northern Bolivia have been poisoned with mercury from fish in the nearby river. Despite the danger to the community - aggravated by a lack of access to health care or alternative food sources - the report showed that the Bolivian government had failed to comply with a 2023 judicial order to stop illegal mining in the area and the use of mercury (banned by the Minamata Convention since 2013).

An investigation by beneficiary Mala Yerba in El Salvador featured in the Bukele: Master of the Skies documentary series by Radio Ambulante, the most influential narrative journalism podcast in Latin America. The episode explored the implications of the adoption of Bitcoin as legal currency in El Salvador and cited the investigation, which showed how Bukele’s government offered to improve the housing of 25 families as part of the scheme. However, the families were then only offered public housing three km away, located by a sewage plant, and asked to pay the equivalent of 10,000 US dollars in bitcoin and work 650 hours on construction.

The Oleksandra Technique: On the Road with Ukraine's Nobel Laureate

Ukraine's Nobel laureate Oleksandra Matviichuk embarks on a speaking tour across the US.

Moldova: Workshops Tackle Gender-Based Disinformation

Trainings explore how to identify, tackle and counter the phenomenon.

"Instead of Holding Guns, Let’s Hold Hands"

Regional event brings NGOs together to counteract conflict, instability and insecurity.

BREN Hague Fellowship Week

“We are going to share what we learned with our community and change some lives.”

Taylor Swift, Vladimir Putin and Kids Identifying as Cats

IWPR guide explores how malign actors use gendered narratives to disrupt societies – and lays out techniques to counter them.

New Cyber Resilience Handbook for Women Rights Groups

Guide offers civil society groups practical resources to combat online threats.

IWPR’s Latin America Work Wins Multiple Journalism Awards

Investigations have been recognised by prestigious juries representing the EU, UN and national awards.

IWPR International Women's Day Journalist of the Year

Prize to honour contributors, beneficiaries and partners working in often challenging environments.

Georgia: Peace Prize Winners Tell Tales of Reconciliation

“The root of the intractability of the conflict is the alienation between the parties.”

Lekso Award: Supporting Journalism and Human Rights

Pieces highlight plight of vulnerable and underrepresented communities in Georgia.

Preserving Media Freedom Amid Conflict

Round table highlights cases in which heavy-handed officials prevented access to information.

Gender-Sensitive Reporting in Times of War

New guidelines aim to support journalists in producing ethical conflict coverage.

Ukraine: Supporting Civil Society Oversight

Resources will enable public activists, journalists and ordinary citizens to monitor state expenditures and investigate corruption.

New Centre to Tackle Disinformation in Moldova

IWPR launches one-stop shop for media and civil society to address Moldova’s hybrid threats.

Building Resilience Across the Eastern Neighbourhood

BREN aims to strengthen civil society and enhance the inclusion of women and marginalised groups.

Combating Disinformation in Venezuela

Media and NGO alliance reveals extent to which the issue affects country’s online information space.

Ukraine Justice Report

Countering Disinformation in Moldova

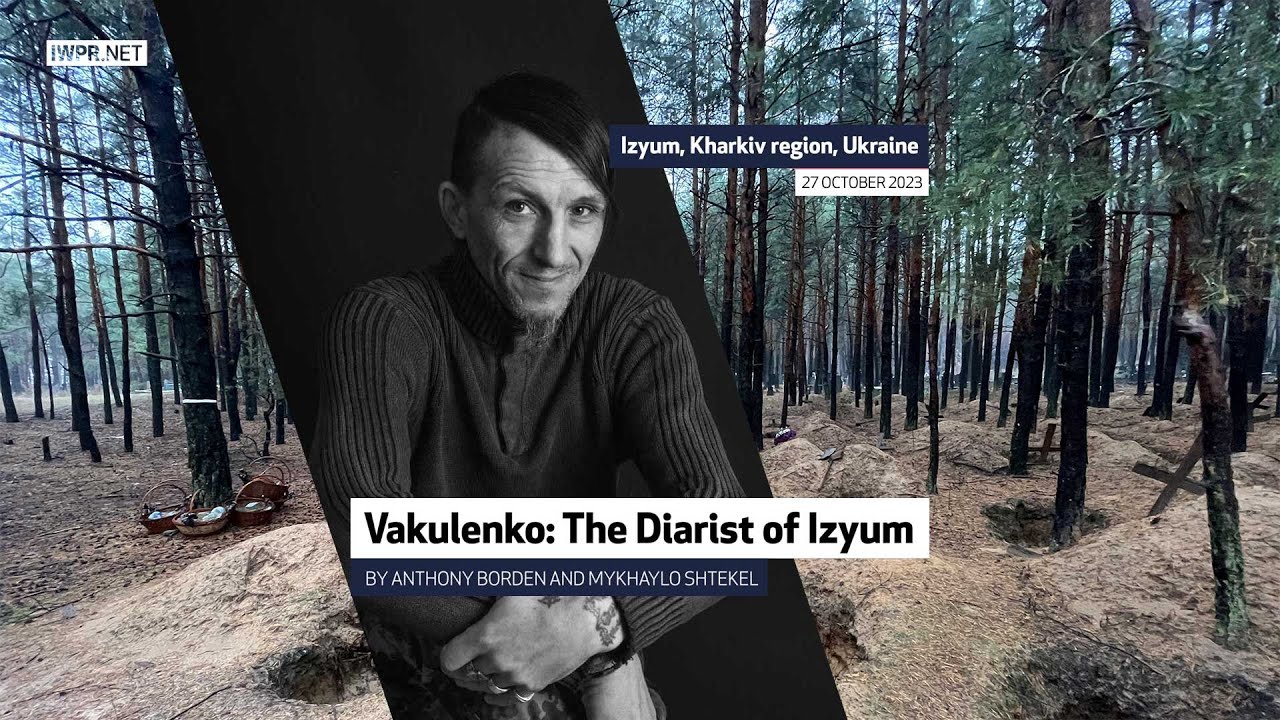

Ukraine War Diary by Anthony Borden

Democratic accountability comes from journalists investigating their own societies – IWPR provides a much needed platform and support for those reporting from some of the most dangerous and difficult places in the world.

Disinformation is a major global threat , especially in conflict and post-conflict areas. IWPR performs a vital mission, building up local voices as a bulwark against this challenge.

IWPR fills a critical gap by helping local journalists to focus on human rights and justice issues. In the process, it contributes to democratic transitions, and demonstrates that the best war reporting is not about military conflict, but human consequences.